Growing a System that Works

Recovery Ecosystem

What is a recovery ecosystem? All the factors that come together to support someone struggling with mental health or substance use issues

Recovery Capital

“Recovery capital (RC) is the breadth and depth of internal and external resources that can be drawn upon to initiate and sustain recovery from severe alcohol and drug (AOD) problems” - Granfield, R., & Cloud, W. (1999). Coming clean: Overcoming addiction without treatment. New York: New York University Press.

There are typically four types of recovery capital working together to support the recovery of an individual. Tools have been developed to assess the amount of recovery capital an individual might have. As the amount of recovery capital increases, so does the likelihood of lasting sobriety and recovery. The goal of the recovery community should be to increase recovery capital for those being supported.

A link to more information on recovery capital and this tool can be found by clicking the image below.

A comprehensive overview of recovery capital can be found here.

Recovery Continuum

Case management, with the guidance of a structured recovery continuum, works to coordinate pieces of the recovery ecosystem. This process must be individualized and guided by the participant. Visualizing where each piece fits helps everyone providing assistance to better understand their role in relation to the overall picture. This helps promote collaboration and can help to engage other members of the community that might have previously understood their role to be independent of the others.

Crisis Response

All too often, at one point or another, a mental health crisis will arise. When this happens, it is important to have robust supportive systems in place. These systems must have the right point(s) to contact, send the right response, and have the right place to go. Without a well structured system that deliberately supports individuals in mental health crisis, the default is law enforcement involvement with a high probability of entrance to the justice system.

Fortunately, Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) are designed to assist communities in developing and implementing these systems. Leveraging the knowledge and expertise of community leaders in law enforcement, mental health services, and advocacy identifies solutions appropriate to meet the needs of individual communities.

Working to identify points at which individuals engage the justice system helps to understand points at which they can be diverted to alternative points of care. Developing a Sequential Intercept Map (SIM) is an important early goal for the CIT steering committee. Only once gaps are identified, can they be addressed. Constant monitoring and data collection within the SIM is vital for measuring its success. No system is ever complete.

Developing the SIM highlights evidence based components that might be missing from the current recovery ecosystem. One such service is a Behavioral Health Urgent Care (BHUC). Much like other urgent care facilities, a BHUC is uniquely equipped to provide specialized services for a specific subset of the population. Rather than utilizing hospital emergency departments or local jails to handle behavioral health crises, these locations are better equipped to truly meet the needs of those in mental health crisis, including those related to substance use. Diverting to a local BHUC can minimize the trauma and unnecessary legal involvement of certain crisis events. This disrupts a cascade of legal and social consequences often associated with law enforcement response to a behavioral health need.

RHA currently operates a BHUC in Asheville, but the need for these services in other rural communities is needed to provide convenient and timely care for those in crisis. It is not always possible for an individual to secure transportation to a destination that is over an hour away, especially in times of crisis.

Access to mental health services is a critical component of the SIM. Provision of these services can take many forms from a stand-alone program, like mobile crisis provided locally by RHA, that can coordinate with first responders, to a co-responder model in which mental health services are dispatched simultaneously to mental health crises, to an embedded model where mental health providers accompany first responders to behavioral health calls. Each model has advantages and disadvantages. It is up to the community to determine which model best serves its citizens.

Reentry Services

Structured resources that provide support and guidance to those with justice involvement are Local Reentry Councils (LRCs). Within the framework of these councils, supported by the NC Department of Adult Correction, individuals can be consistently and deliberately supported before, during, and after their reentry to society. Reentry support has been proven to increase the chances of closing the “revolving door” of incarceration.

Deliberately working to ensure the appropriate services are in place at every point along the recovery continuum increases the chances of success for those served by these systems of care. This includes services that can connect individuals with care during their incarceration. Access to case management while incarcerated is an incredibly effective way to lay the foundation of support and to begin navigation of the complex recovery ecosystem. The U.S. Department of Justice published an article in 1999 outlining case management as it interfaces with the judicial system. Since that time, many justice systems across the country have adopted case management as a way to support their populations and therefore reduce recidivism. Additional information can be found here and here.

Local organizations like Operation Gateway (OG) are also providing “in-reach” services that begin to engage incarcerated individuals before their scheduled release date. Coordinating with case managers located in jails and prisons can allow services like those offered by OG to give inmates a head start in building recovery capital well before their reentry to society.

There is not one magic bullet. It takes the community working together with a clear and well thought out plan.

“The opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety - it’s connection.” - Johann Hari

Start by building or strengthening the communication network

Before undertaking this process, it is important to evaluate what communication systems are already in place within the community. Building upon these networks will identify community partners and accelerate the overall process.

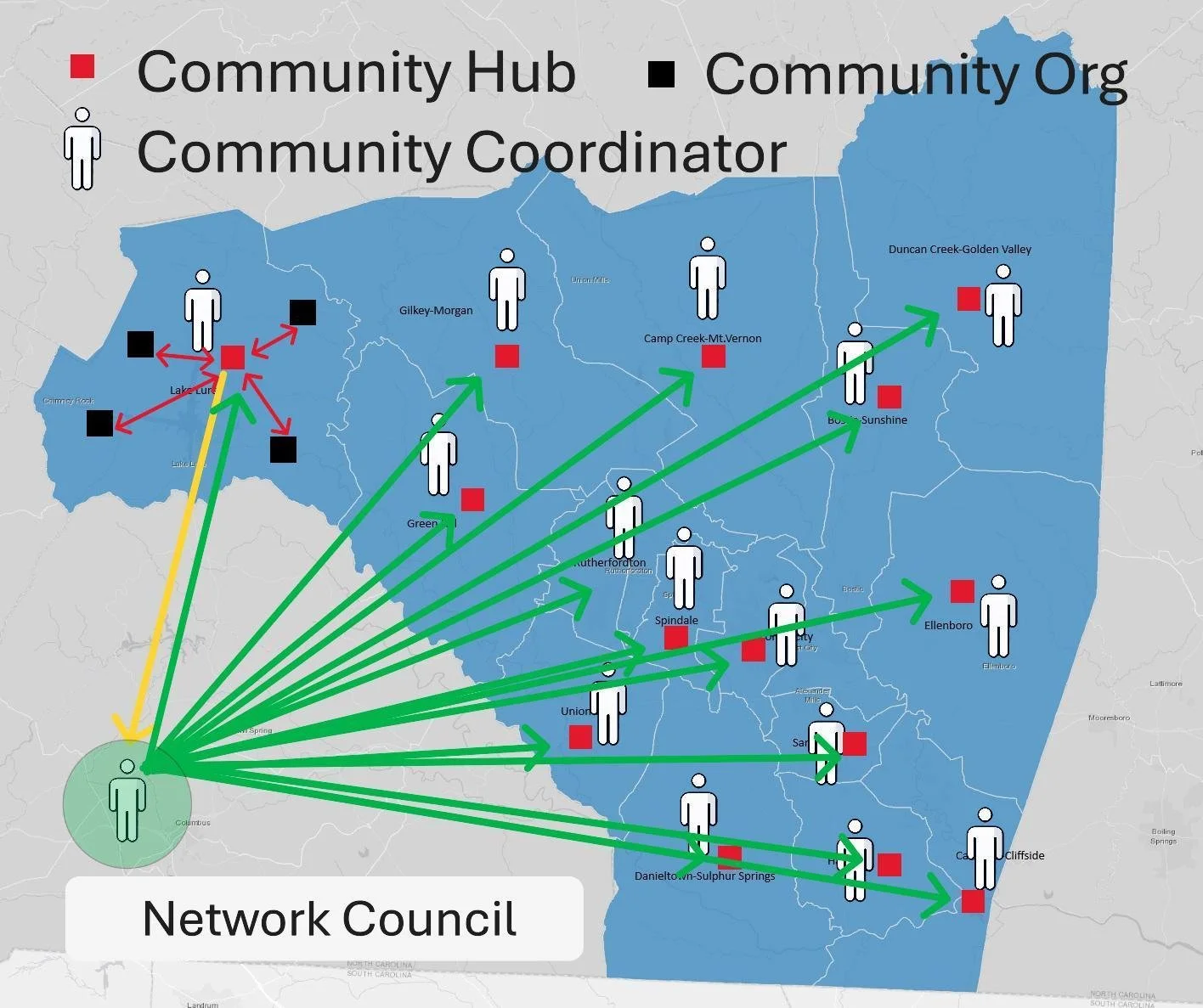

Step 1: Divide the geographic area into districts. The simplest way to do this would be to start with the borders of the county. From here, define districts that take roughly the same amount of time to cross. For example, each district might cover an area that takes 10 minutes to cross by car. This means it would take about five minutes to go from any border of the district to the center.

Step 2: Identify the district centers. This means not only finding the point that is equal distance from the borders, but also a physical building that can accommodate groups that would gather from within the district. Ideal spaces would be churches or community buildings. The location of this space is important in reducing the transportation barriers associated with access to these spaces.

Step 3: Identify the information outlets within each district. These outlets could be churches, community organizations, nonprofits, social groups, and others. Identifying all of these partners will ensure the network reaches the largest possible number of members within the community

Step 4: Develop the process for relaying information. This means not only how will information be distributed to each outlet, but also how each outlet can provide updated information to the network that then distributes it.

This critical step has several factors to consider.

What single contact point or agency receives information from community organizations and outlets? For example, the Community Health Council.

How will information be uniformly presented within the framework of the network? For example, bulletin board spaces, rack cards, display tables, etc.

How will information be consistently delivered to the outlets? For example, email list serves or printed materials given to district leaders to then distributed to outlets within their district.

Work has already begun in developing this network in collaboration with the Multidenominational Coalition of Clergy (MDCC), RoCo Relief, and the Rutherford County Collaborative.

Fortunately, there is already a robust program in place to support organizations that are providing direct services. NC Care360 is a state-wide program that helps to coordinate care for individuals moving between service providers. Promotion and engagement with this program will be instrumental in making sure people are far less likely to “fall between the cracks” when seeking support.

Engaging the Network

Communication must be consistent. This means everyone within the community needs to get the same information about resources, services, plans, and initiatives.

A well-established information sharing network ensures more consistent communication throughout the community. This means developing a process to listen to the needs of the community and then working together to meet those needs. Within this network, a campaign of community education can be promoted and provided to reach the maximum audience. A rotating schedule can be used to ensure community members have multiple opportunities throughout the month to receive the information at a time that fits their schedule. Only once the community is well-informed, can it effectively come together to support its members. Using this information network, a structured year-long curriculum might look something like this:

Month 1: Introduction to Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Activities:

Icebreaker activity to introduce participants.

Overview of the curriculum.

Setting ground rules for respectful and supportive discussions.

Integrated Programs:

NAMI Basics presentation (overview of mental health conditions and resources).

Month 2: Understanding Mental Health

Activities:

Group discussion on personal experiences and perceptions.

Interactive presentation on mental health statistics and facts.

Integrated Programs:

NAMI In Our Own Voice presentation (personal stories of recovery).

Trends in Substance Use/Misuse presentation (general and local statistics).

Month 3: Mental Illness and Its Myths

Activities:

Myth-busting activity.

Q&A with guest speaker (e.g., mental health advocate).

Integrated Programs:

NAMI Ending the Silence presentation (addressing myths and misconceptions).

Month 4: Substance Use Disorder

Activities:

Presentation on substance use disorder statistics.

Discussion on societal views and stigma.

Integrated Programs:

Addiction/Recovery 101 presentation (overview of substance use disorders).

Month 5: Recognizing Signs and Symptoms

Activities:

Role-playing scenarios.

Handout with resources and helplines.

Integrated Programs:

QPR Training (Question, Persuade, Refer for suicide prevention).

Month 6: Treatment Options for Mental Health

Activities:

Panel discussion with mental health professionals.

Interactive Q&A session.

Integrated Programs:

NAMI Family and Friends presentation (supporting loved ones).

Month 7: Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

Activities:

Guest speaker (e.g., person in recovery).

Group discussion on challenges and support strategies.

Integrated Programs:

CCAR Recovery Coach Academy (training on recovery coaching).

Month 8: Co-occurring Disorders

Activities:

Presentation on co-occurring disorders.

Group activity analyzing case studies.

Integrated Programs:

Peer Support Training (understanding and supporting individuals with dual diagnoses).

Month 9: Building Resilience and Coping Skills

Activities:

Workshop on mindfulness and relaxation techniques.

Guided practice session.

Integrated Programs:

WRAP Training (Wellness Recovery Action Plan for self-management).

Month 10: Supporting Loved Ones

Activities:

Role-playing different support scenarios.

Discussion on challenges faced by caregivers.

Integrated Programs:

NAMI Family and Friends presentation (supporting family members).

Month 11: Crisis Management and Suicide Prevention

Activities:

Training on crisis intervention techniques.

Sharing resources and emergency contacts.

Integrated Programs:

Naloxone Training (opioid overdose prevention and response).

Month 12: Building a Supportive Community

Activities:

Group discussion on lessons learned and personal growth.

Celebration and certificates of completion.

Integrated Programs:

Pathways to Recovery presentation (exploring different recovery methods).

FaithNet and Peer to Peer: These NAMI programs can be integrated based on participant interest or specific community needs throughout the curriculum.

Once the communication network is fully operational, and the community is receiving regular and consistent information, coordination of efforts and resources can thrive. More efficient delivery of supportive services like food pantries and ride sharing will allow existing efforts to more effectively serve their recipients. Not only that, but open communication and collaboration illuminates service gaps that can then be closed far more quickly than in the traditional siloed system. Transparent and visible functioning of a truly integrated network breeds HOPE in all it touches.

Lived experience provides an education that is difficult to match within a classroom setting. North Carolina has two extremely accessible training pathways that empower community members by leveraging their lived experience. The Community Health Worker and Peer Support Specialist programs provide a consistent training framework for those seeking to support others using knowledge they have gained over their lifetime.

Peer Support Specialists are people living in recovery with mental illness and / or substance use disorder and who provide support to others who can benefit from their lived experiences. The North Carolina Certified Peer Support Specialist Program provides acknowledgment that the peer has met a set of requirements necessary to provide support to individuals with mental health or substance use disorder

Community health workers (CHWs) are lay members of the community who work either for pay or as volunteers in association with the local health care system in both urban and rural environments. CHWs usually share ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and life experiences with the community members they serve. Since CHWs typically reside in the community they serve, they have the unique ability to bring information where it is needed most. They can reach community residents where they live, eat, play, work, and worship. CHWs are frontline agents of change, helping to reduce health disparities in underserved communities.

All too often people and organizations can lose sight of the individual(s) they are serving. Lack of meaningful personal connections and resulting social isolation is fundamentally at the core of many mental health conditions seen today. Strengthening a system that is able to identify mentors of all ages is of the utmost importance. Organizations such as Big Brothers Big Sisters of America can provide a proven model for developing the pool of mentors available to connect with young people, for example.

Grow the network by identifying leaders and volunteers

Since 1904, Big Brothers Big Sisters has operated under the belief that inherent in every child is incredible potential. As the nation’s largest donor- and volunteer-supported mentoring network, Big Brothers Big Sisters makes meaningful, monitored matches between adult volunteers ("Bigs") and children ("Littles"), ages 5 through young adulthood in communities across the country. We develop positive relationships that have a direct and lasting effect on the lives of young people.

Pairing the after school program with the proven effectiveness of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program creates a robust framework for supporting all children, including those most significantly affected by the substance use epidemic.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure - Benjamin Franklin

Direct services for those in need is only one component of an effective recovery system. Generational cycles can only be broken if efforts are made to identify ways to support the youth. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) or traumas occur in varying degrees to children at every point in our society. Developing a system that builds resiliency in our children is vital to the success of this effort. Coordinating existing community resources around a standardized after school curriculum that supplements skills learned in the classroom can not only provide our children with valuable life skills, but identify ways in which all community members can lend their knowledge and expertise to the future leaders of our communities. An effective curriculum might look something like this:

1. Financial Literacy

Budgeting and managing personal finances

Understanding credit scores and how to maintain good credit

Basics of investing and saving for retirement

Understanding loans, interest rates, and debt management

2. Basic Home Maintenance

Simple plumbing repairs (e.g., fixing a leaky faucet)

Basic electrical work (e.g., changing a light fixture)

Home safety and emergency preparedness

Basic carpentry skills

3. Cooking and Nutrition

Preparing healthy, balanced meals

Understanding nutritional information and dietary needs

Meal planning and grocery shopping efficiently

4. Health and Wellness

Basic first aid and CPR

Maintaining physical fitness

Understanding mental health and stress management techniques

Accessing healthcare services and understanding health insurance

5. Communication Skills

Effective verbal and written communication

Active listening and empathy

Conflict resolution and negotiation skills

Public speaking and presentation skills

6. Digital Literacy

Basic computer and internet skills

Online safety and cybersecurity

Using productivity software (e.g., word processing, spreadsheets)

Understanding digital footprints and responsible social media use

7. Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

Analyzing information and making informed decisions

Creative thinking and innovation

Time management and prioritization

Adaptability and dealing with uncertainty

8. Civic and Cultural Awareness

Understanding rights and responsibilities as a citizen

Basic knowledge of government and political systems

Cultural competence and respect for diversity

Community involvement and volunteering

9. Interpersonal Skills

Building and maintaining healthy relationships

Networking and professional relationship building

Emotional intelligence and self-awareness

Parenting and caregiving skills

10. Workplace Competencies

Resume writing and job interview techniques

Professionalism and workplace etiquette

Project management basics

Understanding workplace rights and labor laws

11. Personal Development

Setting and achieving personal goals

Building resilience and coping skills

Lifelong learning and continuous self-improvement

Understanding and developing personal values and ethics

12. Transportation and Navigation

Basic car maintenance (e.g., changing a tire, checking oil)

Understanding public transportation systems

Reading maps and using GPS effectively

Safe driving practices

13. Emergency Preparedness

Creating and maintaining emergency kits

Developing emergency plans for various scenarios

Understanding local emergency resources and contacts

Basic survival skills (e.g., starting a fire, finding clean water)

This curriculum can be delivered in an age appropriate way beginning in the sixth grade and continuing through the twelfth grade.

Valuable certifications and credentials can be earned along the way.

Children completing this curriculum would be fully equipped to move into independent living after high school.

Implementation of this robust curriculum can provide benefits beyond the skills gained by the children. Offering a safe and structured environment for children in the hours after the formal school day ends can provide stability that may be absent at home. Collaborations with local area mental health providers could make mental health support available to the youth at this time as well. This can greatly reduce the transportation barrier associated with seeking treatment. It can also minimize the disruption to the class time routine for those who might already receive mental health support during the school day.

One very tangible benefit, especially to the working parents, would be childcare that more closely mirrors the standard work day. Often, childcare is a significant challenge for the parents who might be struggling with mental health concerns themselves. Providing this support can have a positive chain reaction across the community as secondary benefits reach the parents of these children.

Organizations such as the YMCA has a longstanding tradition of providing youth support and development. However, not every community has a robust YMCA presence. Partnering with organizations like YMCA can serve to provide structure and support for many community initiatives, including a widespread after school program such as this.